Man I kinda miss Minneapolis. It’s kinda tight.

I tend to do 60 mph coming off of the Lyndale/Hennepin 94 East exit, paying no mind to what’s on either side of me besides traffic. So when Google Maps told me to bust a right onto Ontario Avenue en route to the Rare Form Mastering studio, the turn was as abruptly eye-opening as my conversation with Alec Ness.

Tucked away off of that exit is a small commercial building next door to Sisyphus Brewing. At the end of a narrowly curled hallway on the second floor of that building is one of two studios where Alec, possibly Minneapolis’ most prolific music engineer, gets busy.

Casual music listeners likely don’t know what mastering — the finalization of a musical record — is. And if they do, they might struggle distinguishing it from the more involved mixing process. The thrill of a record’s conception has faded by the time it reaches Alec, but he’s not a lifeless nerd with a laptop.

Alec is the last person to treat what is now a head-down baby ready to be born, and he does it with the kind of love and care this analogy suggests. It’s the same level of compassion, the same people-over-data belief, he treats this city with.

But what exactly is there to appreciate about Minneapolis music today? What is it about our “flyover” city that has captured someone who had a career in San Francisco, signed to a label in New York City, is a certified national expert in his field, and has mastered countless songs for platinum-selling rappers and the most exciting acts in indie music?

Twin Cities Music: A Spirit, Not a Sound

There’s a license here to just kinda be you and not focus so much on social climbing that definitely is built into the music scene in other places.

Alec Ness has the luxury of both an inside-out and an outside-in perspective of our music ecosystem. It makes sense that someone with his small-town background and big-city success sees the spirit of the The Cities: that anyone who wants to do music can do music. Much like our breweries, colleges, and sports teams, our artists come in a wide variety, the bigger names don’t squash the smaller ones, and everyone offers something a bit different.

Sure, global hitmakers aren’t coming and going like they were in the 1980s. But when the attention is turned inward, it becomes apparent that Minneapolis is a cultural beacon to millions of surrounding people who are even more of an afterthought nationally.

Alec himself is from North Dakota. In his first Twin Cities stint, he attended the now-closed McNally Smith College of Music and formed a strong bond with St. Paul-bred Dizzy Fae. After years in San Francisco as avant-garde electronic artist Su Na, he came back and found even more success as the guy polishing other people’s records. What he’s been able to make of our creative economy is a story that asks Minneapolis to believe in itself.

“People literally ask me if we have electricity [in the Dakotas]. I’m like, ‘Are you serious?’

“[Minneapolis is] this Mecca in the middle of a lot of states that don’t have very much going on. A lot of kids move here, like I did, ’cause I was like, ‘Well that’s where all the cool shit is happening, so I’m gonna move to Minneapolis.’ I don’t know if San Francisco and LA and New York have that. They have a much different fabric to them … here, a lot of the young people are made up of international students or people in the surrounding area. It’s people that end up here for maybe different reasons then they would end up in [New York or LA].”

Since the pandemic, highlights for Alec’s mastering work include a track featuring former Migos member Offset, a record for Dreamville’s Bas, and plenty of work with Dua Saleh, one of the city’s more successful artistic exports in recent memory. But his social media presence is subtle on the résumé and big on gratitude, studio adventures, and cheerleading for collaborators big and small. There is very little, if anything, Alec is taking for granted in his second Twin Cities chapter.

“I had lived here for a little while, it’s like, ‘Man, I kinda miss Minneapolis. It’s kinda tight.'”

“I was living in San Francisco. I was like, ‘This is great,’ but I’d tell people there are swimmable lakes in the middle of the city and they were like, ‘There’s no way.’ … They’d picture Lake Merritt in Oakland and they’re like, ‘That’s disgusting, you swim in the lake?’ and I’m like, ‘No, it’s not like Lake Merritt! It’s cleaner.'”

At the mention of lakes, I told him his 2016 EP Surface came to mind. It wasn’t his latest work, but Surface sounds as enchanting and untroubled as the image Alec painted for baffled San Franciscans.

“That was right when I moved back here. That was definitely the vibe I was on. I stopped here and I was just enjoying being here so much. I was on a month-to-month, I was like, ‘I’m just gonna chill here for a little while, New York will be there,’ and seven years later I’m still here.”

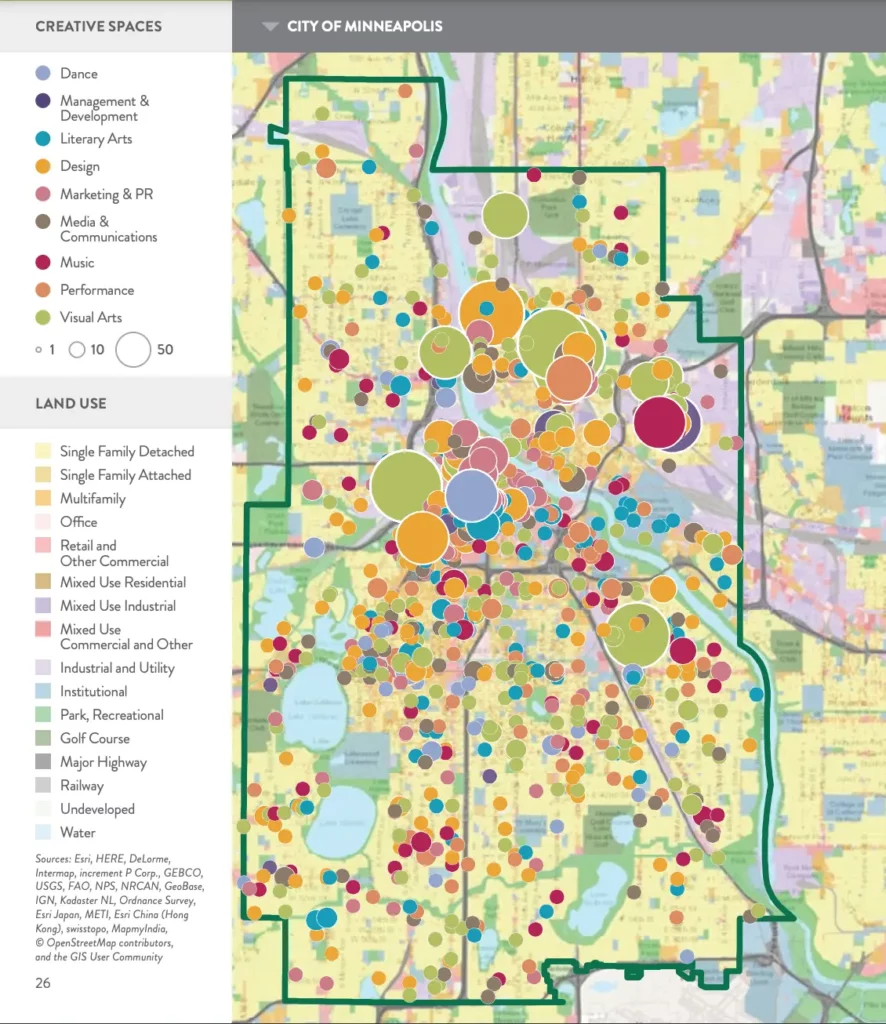

Of the 81,000 people in Minneapolis’ creative economy (city proper), almost 10 percent of them are in music. And there’s at least one music-related business for every square mile in the city, the third-highest such ratio among big US cities. Rent isn’t coastal-level high, you don’t need many connections to get gigs, and our green space and four-season weather offer a lot of ways to escape the grind and find inspiration.

“It’s pretty easy for someone who’s like 18 here to just get a copy of Ableton, make some stuff, and get their stuff on Radio K or whatever. Or at least meet some other like-minded people and make some cool shit. And, I mean … that’s kinda everything.”

Simply put, Minneapolis is a near-ideal place for an aspiring music professional. Locally and beyond, it isn’t talked about like that. Why?

Where Are All These Artists You Speak Of?

If you weren’t following them on social media and they weren’t playing the Entry … you might just not hear about that.

“Accessibility” is a tricky word in both Twin Cities music and the community at large. On one hand, anything you want to do here can be done quickly and affordably. Going from The Bay to The Cities gave Alec the perspective needed to truly love the freedom of Minneapolis music.

“‘Cause in San Francisco, the wall’s really high … It felt like the barrier to entry was much higher because everything’s more expensive, everything’s more limited. Here, it’s maybe wider and a lower wall. It’s easier to get a show here, easier to get in front of people.

“Maybe the stakes are less … the CEO from UMG isn’t gonna be there or something. But with that comes more encouragement or more viability to doing stuff. Because of that we’re spread out a little wider.”

On the other hand, a decentralized artist community means decentralized attention. There is no serious in-crowd you need access to in order to make the most out of Minneapolis. You just need to find … people.

The challenge in a scene with so many equal stages, places, and faces is isolation. Both artists and local music fans struggle to move beyond the pockets of space they’re most familiar with, a tendency that has consequences for our national reputation as a great metro area for music.

The Twins Don’t Get Out Much

Z: “Do you feel like that’s on artists and people that work with artists? Do you feel like there is the hunger? Local residents being like, ‘Yeah man, I like the two local artists I know. But how do I find more?’ Do you feel like there’s enough of that?”

A: “I don’t know … I think artists try really hard here. It’s kinda the dark side of the coin. Maybe this city has not quite the awareness of current music some other cities have.

“If I go to LA and I go hang out at a shop in Los Feliz or something, and I’m like, ‘Hey do you know who Khruangbin is?’, they’re gonna be like, ‘Yeah, of course.’ Whereas if I go — and this is not to insult anybody here — but if I go here and I’m like, ‘Hey, do you know who Kehlani is?’, I don’t know that I’m gonna get the same amount of people out of 10 here that know who Khruangbin or Kehlani is versus LA where that is just so baked into the music culture there. I don’t know if people have quite the awareness here, and maybe I’m not giving them enough credit or talking to the right people.”

This perceived lack of awareness exists on a micro level too. “Best MN Rapper” conversations on social media happen in bubbles where each pocket of the city has a champion with zero challengers. Meanwhile, the local indie pop/R&B acts that get KARE11 coverage exist in an entirely different world, even from similar artists who frequent Icehouse and other go-to venues.

“It seems like people have a harder time corralling an audience to come exist at something here. And it seems like that ripples upward to have a harder time to get national acts to feel the same way here … It feels like they don’t trust us to show up.”

The issue is a collective one. It’s especially telling that someone as directly involved in the creation of as much local music as Alec Ness also finds himself missing out on people and events he would like to support.

“When you’re in London, you can go on Resident Advisor, see everything that’s happening that night, and go out to a club. Here, there’s the First Avenue calendar, maybe … if you’re not following the right people on Twitter, or following the right people on Instagram, or know where to look for the flyer, you’ll just miss stuff here.

“I remember talking to some friends who are … more original hip-hop dudes here. And I remember saying, ‘Man, it’d be cool if there were some kind of global calendar here where people could just throw their events on … I remember them saying that has happened and it’s come and gone.”

Uninterrupted, Alec dug deeper into the local fan struggle. If he were a student at the University of Minnesota, Alec asked himself, how would he hear about his favorite local artist’s shows or discover new ones?

“Say a medium-sized artist … Maybe they’re playing [7th St Entry], like that sized venue. If you weren’t following them on social media and they weren’t playing the Entry, if they were playing a basement or something. Even if they were playing Cedar Cultural Center or something … you might just not hear about that.”

Having a show at Cedar Cultural Center — a venue twice as big as 7th St Entry — go unnoticed is bizarre. Being a local music participant in the Twin Cities can be a multiversal experience where people that should know and connect with each other simply don’t.

Can We Break This Ice?

We have the numbers, quality, and spirit, but how do we pull this artistic sprawl together?

While he might not have the answers, Alec Ness’ awareness of these issues as someone thriving in our scene is valuable. At the very least, it offers validation of many local artists’ experiences from someone on the complete opposite end of the spectrum.

Seriously, the guy does not struggle for work at all.

“I can trace back probably like 20 clients to one person several times over, which is sick.”

Alec’s local-to-nonlocal client ratio is “probably half and half,” which he admits is unusual among local engineers due to his time in San Francisco and as a touring artist. A strong out-of-state network is advantageous, but for someone who masters 15-20 songs per week, the half that are local is no small number.

“I’m so humbled about getting to do what I do because a lot of it has been on the trust of my friends and trust of people that I’ve worked with just saying to their friends or saying to other artists they know, ‘Hey I really trust this guy, you should have him work on your stuff.’ That’s how I get work so many times. And then they recommend me to their friends and then before you know it … I’ll work on something I didn’t even realize was huge.”

Time and good relationships have given Alec a successful free-flowing experience as a local music professional. The formula is simple, but how hard is it to replicate?

“I could sit here and say, ‘It’s easy to get a show here,’ and there’s probably somebody in this town right now that’s like, ‘Man, I’m just tryna get a show.'”

Alec was quick to note gatekeeping exists in every commercial music ecosystem. It’s an industry uniquely based on vibes and capital where a little clout or a little money can quickly become a lot. Just look at how many local venues First Ave owns, a good chunk of them acquired in the last eight years.

That being said, there is something to Alec’s assessment of our music culture. The ease with which people can create and jump onto the scene is everything. We have the numbers, quality, and spirit, but how do we pull this artistic sprawl together? Alec doesn’t claim to have an answer, but we may be able to find one in his habits rather than his mind.

Mastering Mastering: Just Listen To People

“If you think about someone working on a record for like five years and then handing it off to you and being like, ‘You’re the last person to touch this before it goes on streaming,’ that’s a big responsibility! People write breakup songs and songs about people in their lives that passed away. People have really emotional stuff in songs. Or other times it’s just club bangers and they’re like, ‘I just want the 808 to hit like crazy‘.”

Even when pressed about his favorite tools and techniques, Alec preferred to speak about the people he masters for. To Alec, the science of engineering is in emotions as much as it is in hardware and software.

“The ability to match someone at their emotional space is equally as important as learning all the technical stuff.”

Starting out as an artist and producer, Alec’s career as a mastering engineer “fell into my lap.” Years of relationship-building and trustworthiness turned into a steady slew of clients that hasn’t stopped pouring in. Often, someone doing numbers like this is in hot pursuit of fixed goals, many quantifiable. But as he shook around his hockey flow and wisely explained to me, “I don’t feel like I’m really at the wheel as much as I would like to think.”

“I wanted to be a producer for a long time, then I wanted to be an artist for a long time, and I was really pushing down these lanes, you know? I started to let things kind of go the direction they were gonna go and start doing what felt right more.”

In a music scene with so many artists and relatively little overlap, “what felt right” to Alec increasingly became guiding others forward. That, more than anything, is what excites him. With all the knowledge and experience he has, this part of his musical approach might be his most valuable.

“… I’ll have the thing where I hear [a track] and I’m like, ‘I know exactly what I want this to sound like.’ And there’s some really technical steps sometimes that I need to take to get it there, it’s hard to get it there … but when it gets there and it comes out and it’s racking up plays on Spotify, I’m like, ‘Yes.’ This is as good as all [the other music].

“There are times that I’m making a decision on someone’s record for someone I’ve never heard of before who’s from here. It’s their first single or something, they don’t have anything on Spotify. And I’m taking out some mouth clicks or something. I’m so glad that I get to do this for them and get to make this more professional. I don’t even think they’ll notice some of this stuff, but it makes a huge difference. I’m really glad that I’m here to get to step in and elevate this, even another two percent.”

Naturally, I wanted to know where Alec saw himself going in the near future. Just as naturally, his sense of self faded into his sense of community as he answered the question.

“I think right now I focus a lot on the side of not about me or where I’m headed, but more on the side of here, and locally. Especially local artists here. Providing legitimacy from a cultural standpoint like, ‘Oh, this person worked with that artist and they got to do that because their previous record sounded really good’ or whatever. If I can make a collaboration like that happen … awesome. I’m happy to be that small point, a tick on the record.”

* * *

If nothing else, Alec Ness’ career confirms it is possible to thrive in Minneapolis’ music scene. The essence of his success is simple and universal: care about people and be trustworthy. Moving forward, knowledge of Alec’s experience raises bigger questions about local music as a whole.

How easy is it for local music pros to replicate Alec’s success in Minneapolis? How easy do they think it is, and how much does that answer vary from person to person? Ideally, a conversation as fun and useful as this can itself be replicated so we can more quickly figure out how to attract, keep, and support local artists and other music professionals.